Medicine has always sought ingenious ways to restore what nature or misfortune has taken away, but few procedures are as astonishing as the one that has given a man back his sight after 20 years of blindness.

At just 13, Canadian Brent Chapman suffered a catastrophic reaction to ibuprofen, one of the most commonly used over-the-counter painkillers in the world. Millions take it every day for headaches or muscle aches without incident.

But in his case, a rare and devastating side-effect caused severe burns to his cornea. The transparent front layer of the eye, essential for focusing light, was irreparably damaged. An infection later cost him his left eye entirely, leaving his right eye as the only possible candidate for future treatment.

For most people, blindness of this kind results in a lifelong struggle. Everyday activities such as reading, recognising faces, navigating a street become insurmountable barriers. In developed countries, corneal transplants are usually the treatment of choice, but not everyone is eligible. The body can reject donor tissue, while repeated attempts often fail as scarring worsens over time. Mr Chapman underwent almost 50 operations and transplant procedures, each one an attempt to claw back some vision, each one unsuccessful.

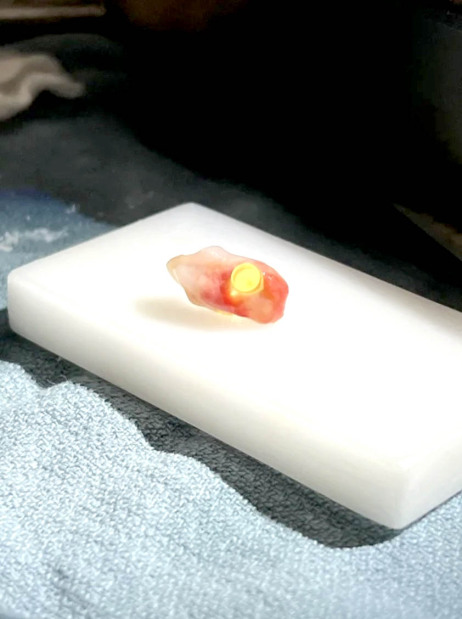

The shaved tooth, embedded with a plastic optical cylinder

Two decades later, however, Surgeons attempted something never before tried in the country: osteoodonto-keratoprosthesis (ODKP), known more colourfully as the ‘tooth-in-eye’ surgery. The operation combines dentistry and ophthalmology in an extraordinary way.

The process begins with the removal of one of the patient’s own teeth, in Mr Chapman’s case, a canine. This tooth, along with a small piece of surrounding bone, provides a sturdy and biologically compatible material. Dr Greg Moloney drilled a precise hole into the tooth and inserted a tiny optical lens. The tooth-lens assembly is then implanted into the damaged eye, effectively replacing the destroyed cornea with a structure capable of channelling light onto the retina.

Why use a tooth? The answer lies in its resilience.

Teeth are naturally strong and resistant to infection. Crucially, because the material comes from the patient’s own body, the risk of immune rejection, one of the greatest challenges of transplant medicine, is vastly reduced. The eye, one of the body’s most sensitive organs, is tricked into accepting this unusual implant because it recognises it as ‘self.’

The result for Mr Chapman has been nothing short of life-changing. With the assistance of glasses, his sight now measures 20/30. To put that in perspective, a person with perfect vision can see an object at 30 feet; he sees the same object clearly at 20 feet. It is a level of vision that allows him to walk unaided, recognise faces, and read signs; all things denied to him for most of his adult life.

“It’s been very emotional. You go so long without seeing and not knowing what things look like anymore,” he said following the surgery. “Being able to see again, it’s exciting. Seeing the city for the first time, seeing people’s faces, it’s like rediscovering everything.”

His reaction is hardly surprising. Studies into blindness show that losing sight is consistently ranked among the most feared health outcomes, alongside dementia and paralysis. The sudden ability to see again after so many years is not simply a medical triumph, but also a profound psychological rebirth.

The surgery is not without its risks. Implanting foreign material into the eye, even if it originates from the patient, always carries the danger of infection or complication. Long-term outcomes are still carefully monitored, and only a handful of surgical centres worldwide have the expertise to perform ODKP. It remains a last resort, reserved for cases in which more conventional corneal grafts or stem cell treatments have failed.

Nevertheless, Canada’s success with Mr Chapman marks a significant milestone. It positions the country among a select group of nations including Italy, where the technique was pioneered, capable of offering hope to those previously told nothing more could be done.

For people living with corneal blindness, which affects millions globally, the breakthrough may inspire new avenues of treatment and international collaboration.

&uuid=(email))